Workplace assessment can benefit from exercise conditioning and yoga sciences: advanced ergonomics practitioners can take a systems approach to better reflect their understanding of complexity and variability in human conditions and work design.

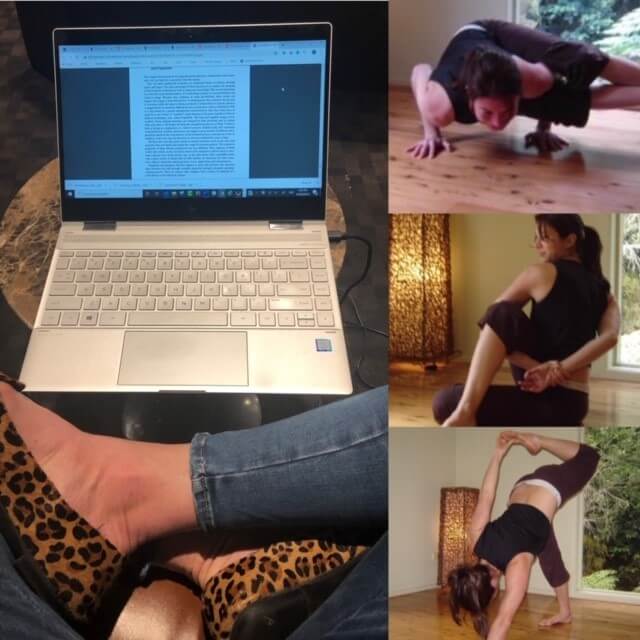

I use the images of myself at right (yoga practice) and while sitting crossed-legged (a yoga sukasana pose) when I wish to challenge students of physical ergonomics studies about their approach to worksite assessment. Too often, assessors approach traditional office-based assessment with a limited scope of view, identifying the hazards of work outside of neutral posture toward awkward ranges as their foundation for a recommendation for change. It is true that awkward postures are a workplace hazard,[i] contributing to possible microtears or damage to muscle, connective tissue, articulating surfaces (joints), and nerve or circulatory structures.[ii] However, the understanding of risk (severity, likelihood, and nature – such as acute or cumulative consequences)[iii] and tissue threshold tolerances (physical work tolerances) requires a more nuanced and complete systems-based analysis. It is the interaction of risk factors that should be concerning when understood in context to overall work performance[iv] and work variety during different operating conditions (busy or “storm season” or short-staffing episodes versus standard operational flow, for example). Risk factors may be compounded by duration of work performance; exertion levels; repetition; psychosocial factors (cognitive-emotional demands of work or motivation and will); individual capability and injury history; or environmental factors[v], [vi] such as thermal conditions[vii], noise, and lighting; and individual sensory profiles (neurological thresholds and capability to modulate or regulate the senses),[viii] for example. There are anatomical and neurological complexities associated with determining tissue tolerance (work capacity).[ix]

Human tissue is animate, it is alive, and it can be conditioned or deconditioned.[x] Work performance can be affected by varied states of capability throughout a day or a periodised micro- or macrocycle of sports conditioning (or time to get accustomed to work demands, for example). [xi] Our “fitness for work” is not binary or dualistic – it is not “on or off”, completely “capable or incapable”, because we have varying states of allostatic regulating neurochemical changes occurring in the body (an interacting series of homeostatic actions). Fatigue and energy states are good examples of this.[xii]

The yoga poses in the images above can represent the conditioning effects of exercise (involving, temporarily, the awkwardness of postures). Constrictions caused by “awkwardness” in postures can assist with shunting (redistributed circulation), mobilisation, co-contraction around a joint, isometric strengthening, a method to activate the core, [xiii] a challenge to proprioceptive and vestibular systems, or a means to reorganise the matrix of myofascial arrangements to support neurochemical, circulatory, and connective and muscular tissue functioning.[xiv] The awkward actions, static and dynamic, can lead to sensations that inform the mind about the physiological condition of the body (a process of interoception) and help resolve emotional states, such as anxiety.[xv] Free nerve endings in the fascial body can project to an insular cortex (different to the somatosensory cortex, a target of proprioception), and affect motivation, a correlation to our emotional well-being.[xvi] The practitioner, therefore, can apply wisdom to explore the awkward, twisting postures, the sensations that arise, and the mindfulness required to return to regulated states in other complementary poses and movements[xvii] (akin to standard workplace advice to move and change postures frequently).[xviii]

Summary

Effective and advanced workplace evaluation requires an understanding of the delicate interplay of physical, cognitive, and organisational systems. At a physical level, complexity exists when determining work tolerances. Collective considerations can be made about work hazards and the interaction of these hazards, but performance capability will vary considerably among individuals (hence, risk refers to probability). Nuanced evaluation is important to human-centred design (this includes involving workers in the analysis – perception matters!). Isolated hazard identification (such as reporting about an awkward posture alone) does not tell a complete story. Risk assessment tools and methods should be sensitive to capture the interaction of risk factors and consequences (acute and cumulative) but also help inform design strategy to achieve work conditioning.

Disclaimer

Sara Pazell, BAppSci(OT), MBA, PhD, CPE, operates a human-centred design consultancy practice. She is affiliated with several Australian universities and service, product, or training organisations. These opinions reflect no other organisation with whom Sara has an affiliation; the ideas, concepts, and opinions are wholly Sara’s (influenced, of course, by the many scholars and teachers from whom Sara has been blessed to learn and sometimes wrangle with intellectually).

[i] Safe Work Australia (2011). Hazardous Manual Tasks Code of Practice. ISBN 978-0-642-33307-0 [PDF]

[ii] Burgess-Limerick, R. (2003). Issues Associated with Force and Weight Limits and Associated Threshold Limit Values in the Physical Handling Work Environment (Commissioned by NOHSC for the review of the National Standard and Code of Practice on Manual Handling and Associated Documents). Brisbane, Qld: UniQuest. http://ergonomics.uq.edu.au/download/threshold.pdf

[iii] Kumar, S. (1999) Selected theories of musculoskeletal injury causation. In Kumar, S. (Ed.). Biomechanics in Ergonomics. London: Taylor & Francis. (pp. 3-24)

[iv] Burgess-Limerick, R. (2003). Issues Associated with Force and Weight Limits and Associated Threshold Limit Values in the Physical Handling Work Environment (Commissioned by NOHSC for the review of the National Standard and Code of Practice on Manual Handling and Associated Documents). Brisbane, Qld: UniQuest. http://ergonomics.uq.edu.au/download/threshold.pdf

[v] Burgess-Limerick, R. (2003). Issues Associated with Force and Weight Limits and Associated Threshold Limit Values in the Physical Handling Work Environment (Commissioned by NOHSC for the review of the National Standard and Code of Practice on Manual Handling and Associated Documents). Brisbane, Qld: UniQuest. http://ergonomics.uq.edu.au/download/threshold.pdf

[vi] Oakman, J., & Chan, S. (2015). Risk management: Where should we target strategies to reduce work-related musculoskeletal disorders? Safety Science, 73, 99 – 105.

[vii] Holmér, I. (2000). Cold stress: Part I – guidelines for practitioners. In Mital, A., Kilbom, A., & Kumar, S. (Eds.). Ergonomics guidelines and problem solving. Amsterdam: Elsevier. (pp. 329-336).

[viii] Engel-Yeger, B., & Dunn, W. (2011). The Relationship between Sensory Processing Difficulties and Anxiety Level of Healthy Adults. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(5), 210–216. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802211X13046730116407

[ix] Burgess-Limerick, R. (2003). Issues Associated with Force and Weight Limits and Associated Threshold Limit Values in the Physical Handling Work Environment (Commissioned by NOHSC for the review of the National Standard and Code of Practice on Manual Handling and Associated Documents). Brisbane, Qld: UniQuest. http://ergonomics.uq.edu.au/download/threshold.pdf

[x] Jeffreys, I., & Moody, J. (Eds.). (2016). Strength and Conditioning for Sports Performance. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN: 9780415578219

[xi] Haff, G. G., & Triplett, N. T. (Eds.). (2015). Essentials of strength training and conditioning: National Strength and Conditioning Association. (4th ed.). Champaign, IL : Human Kinetics. ISBN: 9781492501626

[xii] Caldwell, J. A., Caldwell, J. L., Thompson, L. A., & Lierberman, H. R. (2019). Fatigue and its management in the workplace. Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews, 96, 272 – 289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.10.024

[xiii] Haff, G. G., & Triplett, N. T. (Eds.). (2015). Essentials of strength training and conditioning: National Strength and Conditioning Association. (4th ed.). Champaign, IL : Human Kinetics. ISBN: 9781492501626

[xiv] Myers, T. W. ( 2014) Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meredians for Manual & Movement Therapists. (3rd ed.). Edinburg, UK: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.

[xv] Schleip, R., & Jäger, H. (2012). Interoception: A new correlate for intricate connections between fascial receptors, emotion, and self recognition. In Schleip, R., Findley, T. W., Chaitow, L., & Huijing, P. A., The Tensional Network of The Human Body. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingston Elsevier. ISBN: 978-0-7020-3425-1

[xvi] Berlucchi, G., & Aglioti, S. M. (2010). The body in the brain revisited. Experimental Brain Research, 200, 25 – 35. https://doi-org.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/10.1007/s00221-009-1970-7

[xvii] Borg-Olivier, S., & Machliss, B. (2005). Applied Anatomy & Physiology of Yoga. Waverly, NSW: Yoga Synergy. ISBN: 1-921080-00-0.

[xviii] Buckley J. P., Hedge, A., Yates T., Copeland, R. J., Loosemore, M., Hamer, M., Bradley, G., & Dunstan, D. W. (2015). The sedentary office: an expert statement on the growing case for change towards better health and productivity. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(21), 1357-1362.