Work as a Prescription for Health

Positive design (Desment & Pohlmeyer, 2013) within an occupational framework, is a term that may be used to describe the design of a space, environment, work system, equipment, or tools in such a way that humans, broadly, are beneficiaries. It is an approach in human-centred design, underpinned by participative ergonomics, that provides prosperity, sustainability, diversity, health, wellness, well-being, and wholeness. Positive design can exist along a continuum of workplace strategy stemming from risk management, but it is not just about “designing out risks” or “safety in design”. It is the lens of occupational salutogenesis (the creation of good health and wellbeing) (Antonovsky, 1979; Pazell 2018a) and it means that the design process and outcomes fortify a work space (or community space) and the artefacts with which a person engages: a “humans-in-design” approach (e.g. a term coined by Tristan Cooke, http://humansindesign.com/). In this way, design contributes to health, and it is not simply a means to deter pathology (in which case the perspective is pathogenic and the way most risk management efforts are geared).

- Design for wholeness (Grantham, 2018) provides the means for workers to contribute to a design process (a structured co-design process) so that they are given voice to influence meaningful tasks and environments in which they engage. Design enables the worker to achieve some element of autonomy and control to develop or regulate the best possible work conditions for high-performance.

- Design for well-being (Grantham, 2018) means that work can provide for an emotionally regulated experience, and that we are cognitively challenged to the “just-right” degree. Computer systems are not too clumsy, nor do they present too many barriers; interruptions and distractions are minimal; workload is manageable; communication is transparent and readily understood; recruitment and job performance evaluation is fair and just; lighting is adequate and natural, where possible, to satisfy circadian rhythms and promote optimum performance; noise levels are such that a high privacy index is maintained and concentrated work may occur; and rosters provide for adequate rest and balance yet satisfy the provision of the just-right number of shifts that enable relevance (as a worker) and economic viability (for the worker and system at-large).

- Design for wellness (Grantham, 2018) means that the physical work challenges and requirements are conditioning, not taxing; metabolic conditioning is considered in design (the need to “move” regularly is considered in the design of work); the environmental conditions are health-promoting; and physiological systems with sensory regulation are considered (hearing, touch, vision, taste, or smell externally and vestibular and proprioceptive senses internally). A population may be measured for “wellness” by heart rate, blood pressure, blood glucose or cholesterol levels, body mass index, exercise participate rates, or similar.

- Design for health means that considerations are made for access to good nutrition and fresh foods; consumable, potable water is provided; clean air is available (smoke-free environments, for example); a hygienic workspace is available; the environment allows for spontaneous elimination or toileting (consider the restrictions of rail operators or long shift workers in any industry, for example); or biophilia is built into design (a sense of nature and the natural world), for example.

- Design for diversity provides the conditions to enact effective inclusivity practices. It means that design of work, systems, equipment, or tools is considered for a diverse range of people at present and in the future (in other words, design needs to consider who may be in the workforce in the next twenty years because decisions made now, such as capital equipment purchases, may affect a future cohort). Considerations may be made for anthropometrics (body measurements); functional movement patterns; strength capacities; costume, including wear of personal protective equipment; sex characteristics (male or female); age; injury histories; sensory profile variances; cultural experience; language, literacy, and numeracy; fatigue management and energy systems; knowledge, skills, and ability; decision-making, problem-solving requirements, and heuristics; tactics; distributed situation awareness; inter/intrapersonal skill set demands; occupational press and work factors (urgency, volume, or duration of work); and traditional environmental exposures.

- Design for sustainability represents design that ensures profitability, efficiency, ongoing employment within a community, or ecological balance of natural resources (e.g. the Smart Ocean chair by Humanscale is “net-positive” returning more to the environment than consumption through manufacturing processes). In this vein, operations through to retirement or decommissioning of projects or equipment is important, including material construction that lends to recycling or agile (re)configuration.

- Design for prosperity: this can overlap with many themes described above but essentially means design provides for a fiercely competitive organisational, industry, or national agenda: design is profitable, there is attractive cost benefit and payback, and the humans in the system are fortified, healthful, well, and whole. One effort (profitability) does not exhaust or occur at the expense of the other (wellness and wholeness). The balance is well met.

The design concepts may be complementary or nested within one another yet they each bring a new hue to the occupational lens. Without positive perspectives, design opportunities may be missed.

The practice of ergonomics is often nested within a safety agenda and yet there is so much more opportunity if it were to be considered in multiple business units such as workforce strategy, operations, continuous improvement, finance and procurement, general engineering design, project management, and health and wellness. A positive design approach is occurring in some industries with human-centred design throughout the supply chain (e.g. the Earth Moving Equipment Safety Round Table design philosophy for mining equipment https://emesrt.org/ and the integration of human factors in the Australian rail industry [Transport for NSW, 2015]). In the built environment, the International Well Building InstituteTM promotes health through structural build concepts (and yet the opportunity exists to extend this practice in which human tasks occurring in that environment are central to design consideration).

The risk for non-inclusion (of human-centred work design) in a health and wellness agenda is the advancement of isolated, random, and vulnerable (or ineffective) behavioural-based strategies to address the health (and wellness, well-being, and wholeness, per Grantham, 2018) needs of the workforce. Changing the nature of the work and conditions of the workplace addresses sources of stress: it is inventive and preventive. Changing people is a latent intervention to wrestle with consequences of stress exposure: the action is corrective (Burke, 2014). A behavioural-based approach should not absolve the workplace responsibility to design for effective and high performance (a philosophy supported by the Total Worker Health® strategies, Anger et al, 2015). Certainly, implementation of an organisational-level intervention is a complex undertaking (Wester & Burgess-Limerick, 2015), and this may be part of the reason organisations continually default to individual, behavioural-based programs (Burke, 2014; Kompier et al, 1998; Pazell & Burgess-Limerick, 2015).

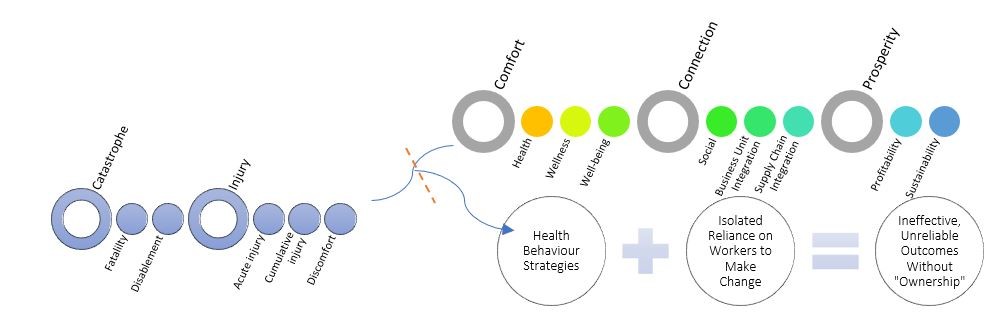

To the bewilderment of advocates of positive, human-centred design practice, the design methods to address good work may seem to fall off a proverbial cliff-face once safety-in-design has been considered. The figure below indicates common industry design practice (particularly heavy industry) and the gap that could be filled by a salutogenic, positive design approach:occ

Figure 1: Adapted from an Occupational Perspective of Health (Pazell, 2018b). The “orange-dash-line” indicates where design strategy and effort often stop and methods are diverted to random behavioural-based strategies. Behavioural intervention, if adopted, could be far more effective if it complemented design that was dedicated to the themes of comfort, connection, and prosperity (and, thus, fulfilled the full-spectrum of the tenants of the Occupational Perspective of Health).

To remain fiercely competitive as a nation, industry, or organisation, there are opportunities to improve our methods. Human-centred approaches may enable design discovery simply by asking, always, what can be done (better and better) to support the humans in the system? Innovative work practice may be fostered by cross-industry and cross-nation learning. Now that technology may be seamless to operations (as much as it may be disruptive in other instances) the opportunities to act on ideas are largely available and possibilities are within reach, if only attention and priority is shifted in this direction.2

Anger, W. K., Elliot, D. L., Bodner, T., Olson, R., Rohlman, D., Truxillo, D. M., Kuehl, K. S., and Hammer, L. B. (2015). Effectiveness of Total Worker Health Interventions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(2), 226 – 247.

Antonovsky, A (1979). Health, Stress, and Coping. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass.

Burke, R., J. (2014). Improving individual and organisational health: Implementing and learning from interventions, Chapter 1, In Biron, C., Burke, R. J., & Cooper, C. L. (Eds.). Creating Healthy Workplaces: Stress Reduction, Improved Well-Being, and Organisational Effectiveness. Surrey, UK: Gower Ashgate.

Desment, P. M. A., & Pohlmeyer, A. E. (2013). Positive design: An introduction to design for subjective well-being. International Journal of Design [Online], 7(3), Available: http://www.ijdesign.org/index.php/IJDesign/article/view/1666/595

Grantham, C. (2018). Is wholeness in the workplace fake news? Work Design Magazine, [Online]: https://workdesign.com/2018/07/is-wholeness-in-the-workplace-fake-news/

Kompier, M., Guerts, S., Grundemann, R., Vink, P., & Smulders, P. (1998). Cases in stress prevention: The success of a participative and stepwise approach. Stress Medicine, 14, 155-168.

Pazell, S. (2018a). Occupational Salutogenesis: A Means to Develop Projects and Sustain Programs that Support Worker Health. LinkedIn Article. Available: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/occupational-salutogenesis-means-develop-projects-sustain-sara-pazell/

Pazell, S. (2018b). Good work design: Strategies to embed human-centred design in organisations. Brisbane, QLD: University of Queensland: Sustainable Minerals Institute.

Pazell, S. & Burgess-Limerick R. (2015). Human-centred design: Integration of health and safety: Part II., Quarry Magazine, November Edition 2015.

Wester, J., & Burgess-Limerick, R. (2015). Using a task-based risk assessment process (EDEEP) to improve equipment design safety: a case study of an exploration drill rig. Mining Technology, 124(2), 69 – 72.

Transport for New South Wales: Transport Assets Standards Authority. (2015, 22 August). Human Factors Integration – General Requirements: T MU HF 00001 ST. Accessed 15 September 2015: http://www.asa.transport.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/asa/asa-standards/t-mu-hf-00001-st.pdf