When things seem messy, as they do when managing the complexity of people and performance, I often look at the fragmented parts and ask, “Are we asking the right questions?”, and “Can our world view be aided by a different lens?”[1]

Health and safety initiatives have been frenzied with excitement because of new literature on occupational psychosocial hazards: the new international standards [2] and the codes of practice,[3] for example. There are codes on managing manual task risks [4] also and on general safety and risk management.[5] These materials are useful when considering hazards and their interaction in the design of work. They can serve as a checklist of factors to consider when examining work. They explain the ‘what’. However, there are some missing pieces that are essential to aid their implementation.[6] We must evaluate the “SO what?” with better assessments of who will be affected, how, and why, and extend “NOW what?” with a meaningful action plan.

By asking, “How do we enhance and optimise human performance?” versus “How do we manage hazards and contain risks?” the world view changes. For me, I see light, not just shadows. It is about how to energise people, optimise performance, and capitalise on motivations and engagement. We must enable the spirited aspects of finding purpose at work so that people may be well and whole. More than this, we can provide a far more effective and integrated way to consider the context of work, its purpose, and the needs of the people involved or affected by that system of work. I often wonder, “When we know that people and systems as a whole are more than their parts, why are work management efforts perpetually focused on fragmentation?”

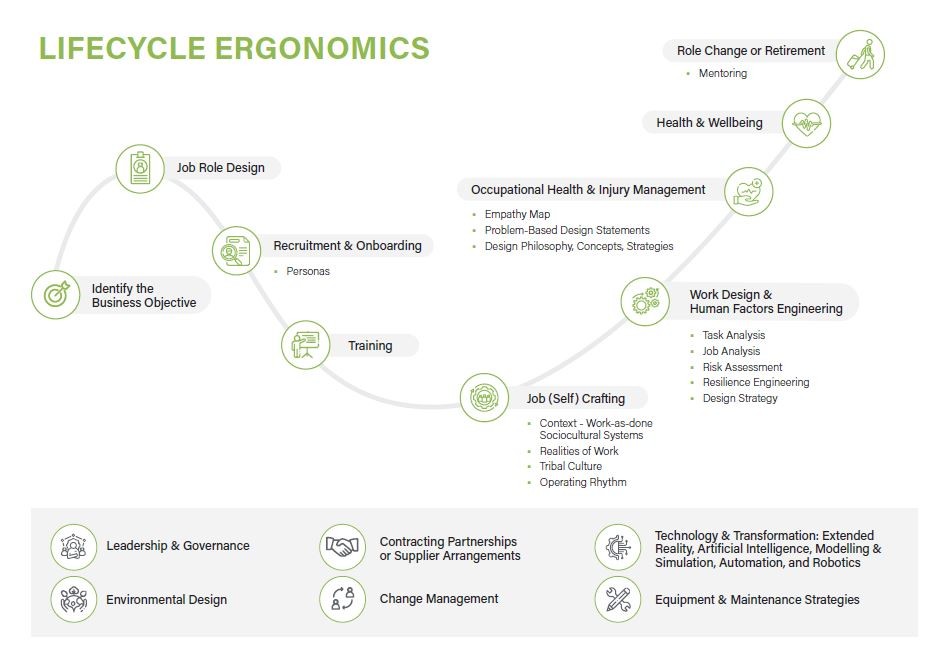

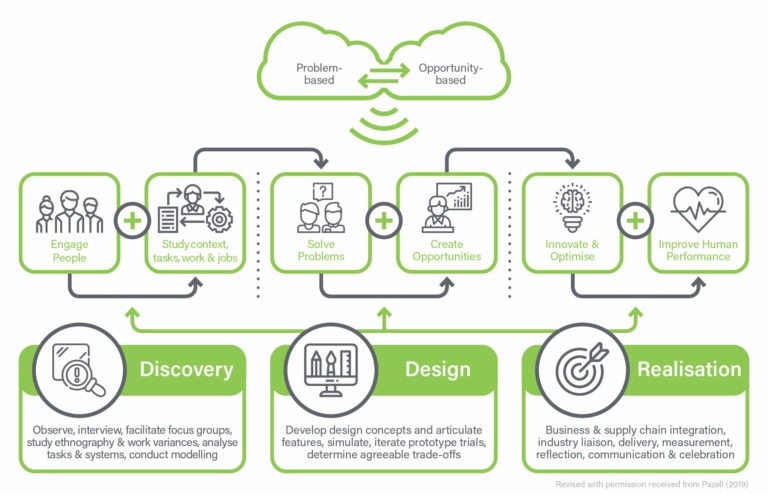

The human-systems approach [7], [8] to advance organisational strategy involves a ‘lifecycle’ orientation to understand people in the business (from hire to retire and every touchpoint within) (Figure 1). In this view, the blueprint for work design begins with the idea of a business or social intention, a whole person, their tribal cultures, and their place and space of being. It is not one fragmented by hazard source, energy type, work exposure, technology interface, or event. The person must be considered in context of the business objective, the recruitment and onboarding, the tasks performed, job role assignment, environment, equipment interface, the technologies, training, work systems, design of work, injury management (when needed), role reassignment or progression, and eventual retirement (Figure 1). Of course, the elements of design supporting these aspects of an employee experience, and even the trajectory of an employee’s experiences, do not necessarily occur in a linear fashion. It is only for the purpose of graphic illustration that a linear journey map is depicted. The consideration of people and their circumstances is diverse, and a wide-lens, systems perspective is required to influence productive, inclusive, and healthful work. Good work design means continuous quality improvement, iterations, testing, trials, and experimentation where learning occurs regularly throughout the design phases of discovery, trials, and realisation of good work [9] (Figure 2).[10]

So, what is one to do? How can the guidance material and literature that are rich in informing us about the work-related human health hazards be leveraged in a meaningful and useful way? Here is a 10-step approach toward intentional leadership through good work design:

- ‘Pause’ the development of fragmented hazard management company policy and procedures. Instead, ask: what happens when we weave (or, better yet, convert) ‘fatigue management’ programs, ‘manual task risk management’ programs, or ‘psychosocial hazard management’ programs into ‘human performance’ and ‘sustainability’ programs?

- Invite skilled work design strategists and those (users) with the experience of their problems in a design process to develop new ways of work; new products, technologies, systems, governance, and so on (Figure 2).

- Identify the business objectives, the company values, and the governance of the systems of work.

- Identify vulnerable populations of workers so that priority can be assigned in ordinate amounts to improve their work experiences (productivity, sustainability, health, and safety).

- Focus on job roles and tasks, environments, and the context of work. Craft detailed job role analyses that integrate physical, cognitive, psychosocial, environmental, social, and contextual factors (like seasonality of work or variations in work exposures in role assignment).[i]

- Apply meaningful risk assessments, coupled with analysis of the critical events of low consequence (but that make the headline news and can bring down a company or an individual). Also, make sure to articulate and strive for the aspirations of great experiences.

- Conduct user group studies in concert with the job analysis: what do people need and want, and why? What is their experience of work? What ideas do they have for work/product/system/environmental improvements that could be harnessed?

- Develop problem-based design statements to consider the user perspective (of many users) while referring to relevant codes, standards, and scientific literature of industry phenomena.

- Evaluate technology with a human performance lens: how will technologies advance human needs and what problems will technology-enhanced work solve?[ii]

- Trial, implement, re-evaluate, learn, and communicate. Prepare to celebrate success and share this knowledge with others.

Imagine the positive impact if we integrated care and quality design to help those who advance organisational strategy: our workers. After all, as soon as a worker commences their career, we have a duty of care [11] and a workplace can leverage well cared for workers as productive assets.[12], [13] If a worker joins an organisation at age 20, they have another 45 years at work or more to interact with the workplace, the artefacts, the technologies, and its people, and these interactions can be constructive if designed well. They have this time to be influenced by lifestyle factors that can also impact on their health and wellbeing, and these factors can be nudged by the design of good work.[14], [15] Translated into a business model, one that is person- (or human-) centred, from hire to retire and every touch point in between,[7] we have an opportunity to derive value from each of our workers and optimise productive return on investment. By realising the business objectives through the effective design of work with systems that promote worker health and capability, we can optimise the value proposition of humans. We can also provide good care for others, which is a societal aspiration of sustainability.[16] Further, we must recognise that skilled humans who are adept at doing the jobs required in many industries are a rare commodity.[17]–[21] As such, a human-centred and technologically enhanced model of work design can foreseeably positively influence recruitment and retention, and impact on the effectiveness and inventiveness of operations while advancing our social values. This is what I have referred to in the past as a ‘human-asset action plan’.[22]

Simply put, it is a philosophical orientation and perspective.[23] I like the idea of gaining something versus losing something: I would rather gain vitality than lose a likelihood of cognitive decline, I would rather gain energy than lose a sense of grogginess and confusion, I would rather live within a breathtaking natural world than just constrain pollutants, and I would rather live well than lose a chance at death. By striving for what we want, we may find the magic in propping all that can bring about change for the better and design for more than just stopping bad things from occurring. If we integrate our approaches in work design, we may model more robust, meaningful, and sustainable strategies and garner greater engagement by those affected by our decisions. When we think of the whole of the person and their experiences, more than an aspect of their brain; part of their body; a social exchange; technology interface; or one of their many places of work, home, study, or play, it will be known that we care.

Disclaimer

Sara Pazell, BAppSci(OT), MBA, PhD, CPE, is the principal work design strategist in a consultancy practice that she pioneered (www.vivahealthgroup.com.au). She is affiliated with several Australian universities and service, product, or training organisations. These opinions reflect no other organisation with whom Sara has an affiliation; the ideas, concepts, and opinions are wholly Sara’s (influenced, of course, by the many scholars and teachers from whom Sara has been blessed to learn and sometimes wrangle with intellectually).

[1] S. Pazell, “Good Work Design: A Conceptual Framework,” ViVA health at work, Apr. 19, 2019. https://vivahealthgroup.com.au/good-work-design-a-conceptual-framework/ (Accessed Apr. 30, 2023).

[2] I. S. O. (ISO), “ISO 45003:2021 Occupational health and safety management — Psychological health and safety at work — Guidelines for managing psychosocial risks,” The British Standards Institution, 2021.

[3] W. H. and S. Queensland, “Managing the risk of psychosocial hazards at work: Code of Practice (QLD),” Workplace Health and Safety Queensland, Queensland, 2022. Accessed: Jan. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.worksafe.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/104857/managing-the-risk-of-psychosocial-hazards-at-work-code-of-practice.pdf

[4] S. NSW, “Hazardous Manual Tasks Code of Practice NSW,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.safework.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/50078/Hazardous-manual-tasks-COP.pdf

[5] W. H. and S. Q. (WHSQ), “How to manage work health and safety risks Code of Practice,” 2021. Accessed: Jan. 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.worksafe.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/72634/how-to-manage-work-health-and-safety-risks-cop-2021.pdf

[6] S. Pazell, “Psychological Risk, Health, & Design,” ViVA health at work, Aug. 22, 2022. https://vivahealthgroup.com.au/psychological-risk-health-design/ (Accessed Apr. 30, 2023).

[7] R. Burgess-Limerick, “Human-Systems Integration for the Safe Implementation of Automation,” Min Metallurgy Explor, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 1799–1806, 2020, doi: 10.1007/s42461-020-00248-z.

[8] Y. Rodríguez and S. Hignett, “Integration of human factors/ergonomics in healthcare systems: A giant leap in safety as a key strategy during Covid‐19,” Hum Factor Ergon Man, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 570–576, 2021, doi: 10.1002/hfm.20907.

[9] N. Karanikas, S. Pazell, A. Wright, and E. Crawford, “Advances in Ergonomics in Design, Proceedings of the AHFE 2021 Virtual Conference on Ergonomics in Design, July 25-29, 2021, USA,” Lect Notes Networks Syst, pp. 904–911, 2021, doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-79760-7_108.

[10] S. Pazell and V. health at work, “Good Work Design,” ViVA health at work, 2019. https://vivahealthgroup.com.au/good-work-design/ (Accessed Apr. 30, 2023).

[11] A. Government, Work Health and Safety Act 2011. 2011.

[12] P. L. Polakoff, “Healthy workers can help make companies productive, profitable.,” Occup Heal Saf Waco Tex, vol. 57, no. 11, p. 16, 1988.

[13] M. Christensen, “The Positive Side of Occupational Health Psychology,” pp. 155–169, 2017, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-66781-2_13.

[14] F. Geaney et al., “The food choice at work study: effectiveness of complex workplace dietary interventions on dietary behaviours and diet-related disease risk – study protocol for a clustered controlled trial,” Trials, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 370–370, 2013, doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-370.

[15] P. D. Cooley, C. P. Mainsbridge, V. Cruickshank, H. Guan, A. Ye, and S. J. Pedersen, “Peer champions responses to nudge-based strategies designed to reduce prolonged sitting behaviour: Lessons learnt and implications from lived experiences of non-compliant participants,” Aims Public Heal, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 574–588, 2022, doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2022040.

[16] T. U. N. D. Program, “The Sustainable Development Goals in Action,” Sustainable Development Goals Integration, 2015. https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals (Accessed Apr. 30, 2023).

[17] J. B. Kirst, “Taking a Balanced Approach to the Technical Skills Gap,” J Petrol Technol, vol. 66, no. 01, pp. 60–61, 2014, doi: 10.2118/0114-0060-jpt.

[18] F. Goupil, P. Laskov, I. Pekaric, M. Felderer, A. Dürr, and F. Thiesse, “Towards Understanding the Skill Gap in Cybersecurity,” Arxiv, 2022, doi: 10.48550/arxiv.2204.13793.

[19] J. Bridges, P. Griffiths, E. Oliver, and R. M. Pickering, “Hospital nurse staffing and staff-patient interactions: an observational study.,” Bmj Qual Saf, vol. 28, no. 9, pp. 706–713, 2018, doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008948.

[20] S. Okoroafor, S. Ngobua, M. Titus, and I. Opubo, “Applying the workload indicators of staffing needs method in determining frontline health workforce staffing for primary level facilities in Rivers state Nigeria,” Global Heal Res Policy, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 35, 2019, doi: 10.1186/s41256-019-0125-z.

[21] S. Nyce, “Workforce Planning for a Global Automotive Economy,” Ssrn Electron J, 2006, doi: 10.2139/ssrn.911517.

[22] S. Pazell, “A human asset action plan (HAAPy),” ViVA health at work, May 27, 2017. https://vivahealthgroup.com.au/?s=haapy (Accessed Apr. 30, 2023).

[23] J. A. Golembiewski and J. Zeisel, “The Handbook of Salutogenesis,” pp. 513–532, 2022, doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-79515-3_48.

——

[i] Work with experienced human factors and certified professional ergonomists for robust support in these matters.

[ii] Consider the sizzle not the steak of technology: Technology for technology’s sake does not solve business and world problems.